Taking control of bronchial asthma: a patient case study

Patient case study:

The photographs and name used are not those of a real patient and are for illustrative purposes only.

''Breathe in. Breathe out. Close my eyes to take all the sensations in. The distant singing of birds, and the sun’s warmth hitting my face as it rises over the horizon. That’s how I imagine it will feel at the top of the hill I see from my kitchen window. Every month, my local walking club heads up to the top, and tell me how breathtaking it is to watch the sunrise. I never thought I would be able to experience this. But this year is different."

Isabel, Asthma patient

A formidable ascent tells the story of Isabel, a woman in her sixties, who has always dreamed of joining her fellow walkers on the trail up a hill with a spectacular view, beloved by locals and tourists alike. She looks up at it every day whilst washing the dishes, imagining what it would be like to finally stand at its highest point and see golden beams of sunlight over the valley, and her home below. But, for Isabel, long walks are hard, and she finds herself feeling breathless before she’s reached the top. Could the answer be in changing her asthma management?

This story has been adapted from a patient case treated by Dr. Abel Pallarés-Sanmartín, Head of Service of the Pulmonology Department, Ourense University Hospital Complex, Spain. This is only an exemplary patient case study for illustrative purposes. Effect and experience of any treatment may vary for each individual patient. Appropriateness of treatment has to be decided by the treating physician on a case by case basis.

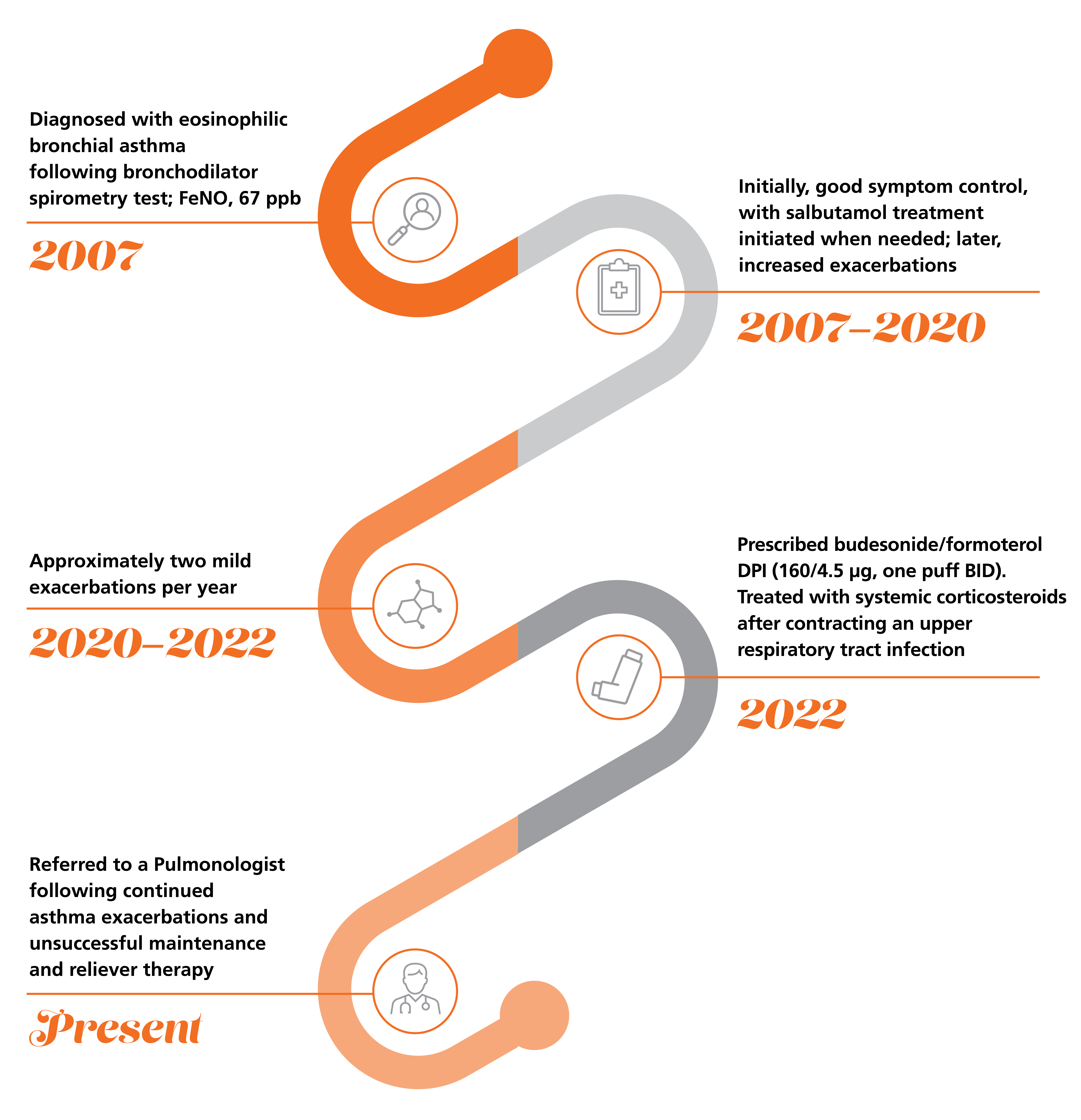

Isabel’s journey so far

Isabel first began noticing symptoms over 15 years ago. Isabel was used to being on her feet all day, but she had begun to find her busy workload harder than before. She often became out of breath whilst carrying out the smallest tasks, such as walking up the stairs in the office blocks.

She made an appointment to see her Primary Care Physician, and after a full diagnostic workup, Isabel was told she had eosinophilic bronchial asthma.

With a plan in place, Isabel managed her symptoms for over a decade, continuing her cleaning business and trying to build up her strength to conquer the challenging hill.

But, two years ago Isabel's exacerbations began to increase. She tried following her action plan as best she could, but her symptoms escalated, and soon she was experiencing mild exacerbations approximately two times per year.

Her doctor prescribed budesonide/formoterol DPI (160/4.5 µg, one puff BID) to try and control her asthma and Isabel was hopeful that her symptoms would soon clear. However, after six months, she contracted an upper respiratory tract infection and was treated with corticosteroids. One month later, Isabel continued to have exacerbations, and was prescribed maintenance and reliever therapy.

Despite treatment, Isabel required emergency assistance with nebulisations and systemic corticosteroids, and was referred to a Pulmonologist.

Abbreviations

BID, twice daily; DPI, dry powder inhaler; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; ppb, parts per billion.

Clinical presentation

Following advice from her Primary Care Physician, Isabel visited the Pulmonologist. She reported high levels of anxiety because her asthma had become poorly controlled. This was reflected by her ACT score of 13, where she was experiencing greater symptoms in the afternoon and at night. Despite using her maintenance inhaler 6-7 times/day, Isabel had suffered from three exacerbations in 12 months and had received 450 mg of oral corticosteroids.

Whilst Isabel had a basal O2 saturation of 97%, a lung auscultation showed end-respiratory wheezing. Rhinitis, sinusitis, gastroesophageal reflux, polyps, septum deviation, and nocturnal apnoea were ruled out, along with confirmation that she had no allergic sensitisations. After checking her inhalation practice with the In-Check Dial, her Physician noted that she did not have the ability to successfully perform the inhalation.

Isabel was diagnosed with late onset severe eosinophilic persistent asthma, without allergic sensitisation and with poor control.

What other comorbidities are present in Isabel’s medical history?

| Perennial rhinitis |

| Anxiety, treated with lorazepam |

- BMI: 22 kg/m2

- Blood eosinophil count: 450 cells/µL

- Skin prick test: No allergic sensitisation

- ACT score: 13;

Desirable range ≥201* - HADS test score: 15;

Desirable range ≤72**

- FEV1: 1650 mL (77%);

post-bronchodilator: +280 mL (+13%);

Desirable range ≥80%3† - FVC: 2480 mL (93%);

Desirable range ≥80%3† - FEV1/FVC: 66%;

Desirable range ≥70%3 - FeNO: 46 ppb;

Desirable range <25 ppb5‡

- Chest X-ray:

No acute pleuroparenchymal abnormalities

*≥20 indicates controlled asthma, 16-19 indicates partly controlled, <16 indicates uncontrolled1

**A score of 7 or less is considered normal, while 8-10 indicates borderline/mild cases and 11-21 is abnormal, indicating anxiety and/or depression.2

† >70% pred indicates mild airways obstruction, 60-69% pred indicates moderate, 50-59% pred indicates moderately severe, 35-49% pred indicates severe, <35% pred indicates very severe.4

‡25-50 ppb is considered intermediate and > 50 ppb is high, indicating airway inflammation5

Abbreviations and References

ACT, asthma control test; BMI, body mass index; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; ppb, parts per billion.

1. Soler X, et al. Allerg Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):151–158.

2. Rishi P, et al. Indian J Ophalmol. 2017;65(11):1203–1208.

3. Barreiro TJ and Perillo I. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(5):1107–1114.

4. Quanjer PH, et al. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:505–512

5. Miskoff JA et al. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4864.

Treatment decisions

Without control of her symptoms, Isabel’s dream of conquering the hill was feeling even more unreachable. Her Pulmonologist determined that a change in therapeutic strategy was vital.

After determining that Isabel’s inhalation technique was insufficient and taking her reduced inspiratory capacity into consideration, treatment was stepped-up to a high dose of corticosteroids and was switched to a pMDI from a DPI. Given the lack of symptomatic control achieved with Isabel using her inhaler as maintenance and reliever therapy (MART),1 her doctor chose to initiate flutiform® (fluticasone propionate/formoterol) pMDI 250/10 µg, 2 puffs BID, alongside a SABA reliever.

Isabel was additionally given guidance on how to use her inhaler correctly. Through improved control of her asthma, Isabel could remove one potential source of anxiety2, and be empowered to enjoy the things she so longed to do.

Abbreviations and Reference

BID, twice daily; DPI, dry powder inhaler; pMDI, pressurised metered-dose inhaler; SABA, short-acting ß2 agonist.

1. Chapman KR, et al. Thorax. 2010 Aug;65(8):747-52.

2. Del Giacco SR, et al. Respiratory Medicine 2016.120:44-53.

Why flutiform® (fluticasone propionate/formoterol) pMDI?

flutiform® pMDI was chosen to help treat Isabel’s uncontrolled asthma because it demonstrates:

Low rates of severe asthma exacerbations1–5

- flutiform® pMDI demonstrates low rates of severe asthma exacerbations across RCTs1 and RWE studies, compared to other ICS/LABA combinations1–4

- A meta-analysis conducted in 2022 showed flutiform® pMDI reduces the risk of severe asthma exacerbations and increases the odds of achieving asthma control in real-world asthmatic patients5

Stay informed about flutiform® pMDI asthma exacerbation treatment.

Significant improvements in asthma control in a real-world setting2–4,6

- Observational studies demonstrate that flutiform® pMDI treatment increases the proportion of patients with well-controlled asthma from baseline, which more than doubles after 12 months of flutiform® pMDI treatment2,3

- A significantly higher proportion of patients achieved controlled asthma after switching from fluticasone propionate/salmeterol to flutiform® pMDI6

Discover information on real-world evidence for improved asthma control with flutiform® pMDI.

Greater persistence and adherence to treatment4

- Patients receiving flutiform® pMDI have been associated with a greater adherence to treatment vs. other ICS/LABA combinations4

Explore flutiform® pMDI asthma management video platform.

View flutiform® pMDI safety profile.

- Safety and tolerability of flutiform® pMDI has been well established during clinical development and adverse events are available in the flutiform® pMDI Prescribing Information. 7

Abbreviations and References

ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting ß2 agonist; pMDI, pressurised metered-dose inhaler; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RWE, real-world evidence.

1. Papi A, et al. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2016;29:346–361.

2. Schmidt O, et al. Respir Med. 2017;131:166–174.

3. Backer V, et al. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1–16.

4. Sicras-Mainar A, et al. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e053964.

5. Papi A, et al. Eur Clin Resp J. 2023;10(2174642):1–10

6. Usmani O S, et al. J Allerg Clin Immunol Prac. 2017;5(5):1378–87.

7. flutiform® SmPC. Last updated April 2022. https://www.emcpi.com/pi/26954 [Accessed June 2024].

Isabel’s outcome

It has been a year since Isabel had her consultation with the Pulmonologist, and she feels that her asthma management has been improved. Her inhaler technique is much more effective, and her improved spirometry and FeNO results have been maintained. With minimal need for rescue medication, Isabel hasn’t experienced another exacerbation, and no longer requires oral corticosteroids.

Finally, Isabel is able to join her fellow walkers as they make their way up the hill path, determined to catch the sunrise at the top.

Since initiating flutiform® pMDI, Isabel has been able to take control of her asthma symptoms. With an ACT score of 23, she has noticed considerable improvements in her symptoms, and her improved lung function and FeNO levels have been maintained. Above all, she has not experienced any further exacerbations, offering a treatment improvement by removing the need for rescue medications and oral corticosteroids.

Before flutiform® pMDI initiation+:

Image

|

|

Image

|

|

After flutiform® pMDI initiation+:

Image

|

|

Image

|

|

+In this patient improvements in FeNO and HADS were a secondary benefit. The effects of flutiform® on FeNO and HADS have not been investigated in clinical trials.

*≥20 indicates controlled asthma, 16-19 indicates partly controlled, <16 indicates uncontrolled1

**A score of 7 or less is considered normal, while 8-10 indicates borderline/mild cases and 11-21 is abnormal, indicating anxiety and/or depression.2

†>70% pred indicates mild airways obstruction, 60-69% pred indicates moderate, 50-59% pred indicates moderately severe, 35-49% pred indicates severe, <35% pred indicates very severe.4

‡25-50 ppb is considered intermediate and > 50 ppb is high, indicating airway inflammation5

Abbreviations

ACT, asthma control test; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; HADS, hospital anxiety and depression scale; pMDI, pressurised metered-dose inhaler; ppb, parts per billion.

1. Soler X, et al. Allerg Clin Immunol Pract. 2018;6(1):151–158.

2. Rishi P, et al. Indian J Ophalmol. 2017;65(11):1203–1208.

3. Barreiro TJ and Perillo I. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(5):1107–1114.

4. Quanjer PH, et al. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:505–512.

5. Miskoff JA et al. Cureus. 2019;11(6):e4864.

Key Takeaways

Optimal asthma management could improve the lives of patients like Isabel.

How can you take steps to help your patients manage their asthma, allowing them to keep doing what they love most?

Look out for your uncontrolled patients

- Isabel suffered from uncontrolled asthma with several exacerbations per year, poor inhaler technique and frequent side effects

- Unfortunately, Isabel’s case is not unique. Many asthma patients overestimate their symptom control and underestimate the severity of their condition, tolerating symptoms and lifestyle limitations1

Determine factors contributing to poor symptom control

- Adherence with asthma treatment is typically low at around 30–50%, which can lead to poor symptom control.2 In Isabel’s case, her anxiety was a barrier to her achieving control of her symptoms, and her inhaler technique required improvement

- After determining relevant comorbidities and before amending the dose of medication in a patient, adherence to treatment should be reviewed. Inhalation technique should be assessed, and training conducted where needed3

Assess, adjust, review

- Personalising Isabel’s asthma care was key to improving her adherence, technique, and symptom control

- After assessing your patients’ relevant comorbidities, inhaler technique and diagnosis, it is vital to investigate their personal preferences and desired outcomes from treatment4

- Regularly review symptoms, exacerbations, side effects, lung function and patient satisfaction

Abbreviation and References

pMDI, pressurised metered-dose inhaler

1. Price D, et al. Prim Care Respir J. 2014;24:14009.

2. Bidwal M, et al. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2017;13(4):759–766.

3. Price D, et al. Respir Med. 2013;107(1):37–46.

4. Baggot C, et al. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8):e037491.

5. Usmani O S, et al. J Allerg Clin Immunol Prac. 2017;5(5):1378–87.

6. Schmidt O, et al. Respir Med. 2017;131:166–174.

7. Backer V, et al. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2018;12:1–16.

8. Sicras-Mainar A, et al. BMJ Open. 2022;12(4):e053964.

®: FLUTIFORM is a Registered Trademark of Jagotec AG and used under licence by Mundipharma.

®: The ‘lung’ logo, is a Registered Trademark of Mundipharma

Dr. Abel Pallarés-Sanmartín biography:

Dr. Abel Pallarés-Sanmartín is the Head of Service of the Pulmonology Department and coordinator of the asthma unit at the Ourense University Hospital Complex in Ourense, Spain. Before taking on this role, he coordinated key multidisciplinary asthma units in Vigo and Pontevedra, and has accumulated 15 years of expertise in the management of severe asthma. Besides his medical practice, Dr. Abel Pallarés-Sanmartín has published extensive research into asthma management and has spoken professionally at national and international conferences.